Vulcan was a proposed planet that some pre-20th-century astronomers believed existed in an orbit between Mercury and the Sun. Speculation about intermercurial bodies—objects orbiting inside Mercury’s path—dates back to the early 17th century. Although the planet was never confirmed, it was seriously considered due to unexplained anomalies in Mercury’s orbit.

Early Observations and Hypotheses

In 1611, German astronomer Christoph Scheiner reported seeing objects crossing the Sun, though these were later identified as sunspots. Other early claims included a sighting by British lawyer and amateur astronomer Capel Lofft on January 6, 1818, who described “an opaque body traversing the sun’s disc.” Bavarian physician Franz von Paula Gruithuisen reported two dark spots on the Sun on June 26, 1819. German astronomer J.W. Pastorff also made several observations between 1822 and 1837, including one where he described a spot 3 arcseconds wide and a smaller one of 1.25 arcseconds.

Proposals of intra-Mercurial planets were made by British scientist Thomas Dick in 1838 and by French physicist Jacques Babinet in 1846, who suggested incandescent, planet-like clouds near the Sun. Babinet even proposed the name “Vulcan,” after the Roman god of fire.

Because a planet close to the Sun would be lost in its glare, astronomers tried to catch it during transits—when a planet passes in front of the Sun. German amateur astronomer Heinrich Schwabe searched every clear day from 1826 to 1843 without success. Yale scientist Edward Claudius Herrick began systematic twice-daily observations in 1847. In 1853, French physician Edmond Modeste Lescarbault began his own observations using a 95 mm (3.75-inch) refractor telescope outside his surgery, continuing more systematically after 1858.

Le Verrier’s Theory and Vulcan’s “Discovery”

In 1840, François Arago, director of the Paris Observatory, suggested that French mathematician Urbain Le Verrier investigate Mercury’s orbit using Newtonian mechanics. By 1845, Le Verrier had published a detailed study, which failed to match observations of Mercury’s transits. Undeterred, he published a more comprehensive analysis in 1859, using 14 transits and numerous meridian observations. His calculations revealed a small but persistent anomaly in Mercury’s orbit: its perihelion—the point closest to the Sun—advanced slightly more than Newtonian physics could explain. The discrepancy was about 43 arcseconds per century.

Le Verrier proposed that the anomaly was caused by an unknown mass inside Mercury’s orbit—either a planet or a group of asteroids. His earlier success in predicting Neptune’s existence using a similar method lent credibility to this idea.

On December 22, 1859, Le Verrier received a letter from Lescarbault, who claimed to have observed a transit of an unknown object on March 26 of that year. Le Verrier traveled unannounced to Lescarbault’s observatory in Orgères-en-Beauce. Though skeptical of Lescarbault’s crude equipment, he was convinced by the physician’s report and calculations, which indicated a transit lasting 1 hour, 17 minutes, and 9 seconds.

On January 2, 1860, Le Verrier announced the discovery of the new planet “Vulcan” to the Académie des Sciences in Paris. Lescarbault was awarded the Légion d’honneur and invited to speak before many learned societies.

However, not all were convinced. Emmanuel Liais, observing from Rio de Janeiro with a telescope twice as powerful, reported no such transit at the time claimed by Lescarbault and publicly disputed the observation.

Continued Reports and Failed Predictions

Based on Lescarbault’s observation, Le Verrier calculated Vulcan’s orbit: a circular path 21 million km (0.14 AU) from the Sun with a 19-day, 17-hour orbital period, inclined 12 degrees and 10 minutes to the ecliptic. He estimated its maximum elongation from the Sun to be 8 degrees. Le Verrier adjusted these parameters as more unverified sightings were reported, though future predicted transits failed to materialize.

Numerous amateur astronomers reported unexplained transits, including F.A.R. Russell in London on January 29, 1860, and American observer Richard Covington around the same time. In 1862, amateur astronomer Mr. Lummis in Manchester claimed another transit, supported by his colleague. Based on these reports, French astronomers Benjamin Valz and Rodolphe Radau calculated Vulcan’s orbital period—17 days and 13 hours, and 19 days and 22 hours, respectively.

Another report came from Aristide Coumbary in Istanbul on May 8, 1865. Despite these claims, no reliable observations were made from 1866 to 1878.

The Eclipse of 1878 and Later Disproof

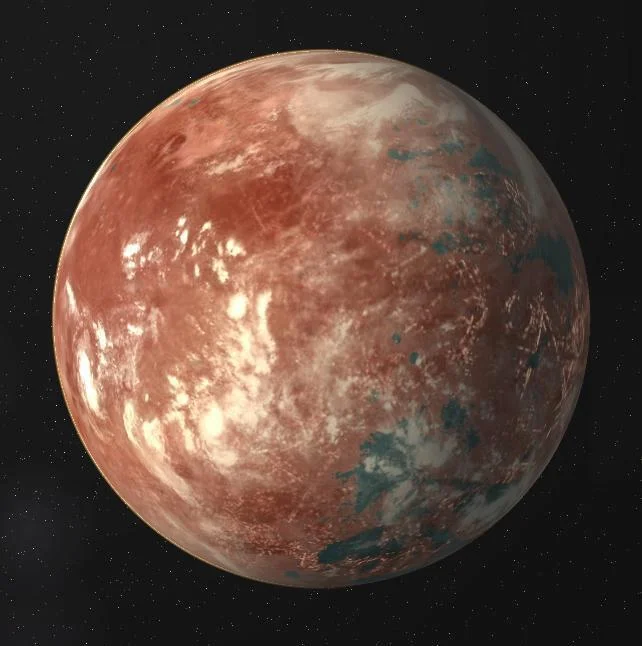

During the total solar eclipse on July 29, 1878, respected astronomers James Craig Watson and Lewis Swift claimed to see Vulcan near the Sun. Watson, from Separation Point, Wyoming, and Swift, near Denver, Colorado, reported seeing a red, planet-like object. Watson described it as having a definite disk, suggesting it wasn’t a star. Both believed they had seen an intra-Mercurial planet.

However, their reported coordinates did not match each other or any known stars. Rival astronomer C.H.F. Peters dismissed the claims, arguing they had likely misidentified bright stars, especially given the observational tools used.

Searches continued during solar eclipses in 1883, 1887, 1889, 1900, 1901, 1905, and 1908. But no further credible evidence emerged.

In 1908, William Wallace Campbell and Charles Dillon Perrine of the Lick Observatory, after extensive photographic studies during eclipses, concluded:

“In our opinion, the work of the three Crocker Expeditions … brings the observational side of the intermercurial planet problem—famous for half a century—definitely to a close.”

General Relativity Ends the Vulcan Hypothesis

In 1915, Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity redefined gravity and resolved the mystery of Mercury’s perihelion precession. The theory predicted a shift of 43 arcseconds per century—precisely matching the observed discrepancy without the need for a hypothetical planet.

Relativity also slightly adjusted the predicted orbits of other planets, though the effect diminished with distance from the Sun. Mercury’s eccentric orbit made its perihelion shift easier to detect than that of Venus or Earth. Einstein’s theory was confirmed observationally during the solar eclipse of May 29, 1919, when Arthur Eddington’s expedition showed that starlight was indeed bent by the Sun’s gravity.

Most astronomers then accepted that no planet existed between Mercury and the Sun.

Modern Searches and the Vulcanoids

Though the planet Vulcan was disproven, the idea of smaller bodies within Mercury’s orbit remains. The International Astronomical Union has reserved the name “Vulcanoids” for any such asteroids. However, despite searches using both ground- and space-based telescopes—including NASA’s Parker Solar Probe—no Vulcanoids have been found to date.